A regression toward the mean year

For 2023, I went back to my happiest place—making July all about family.

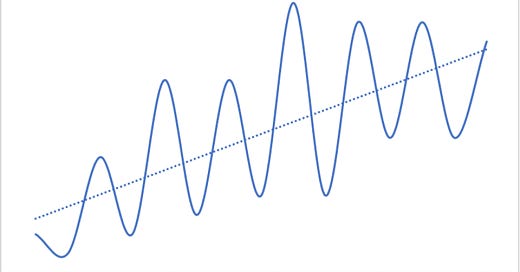

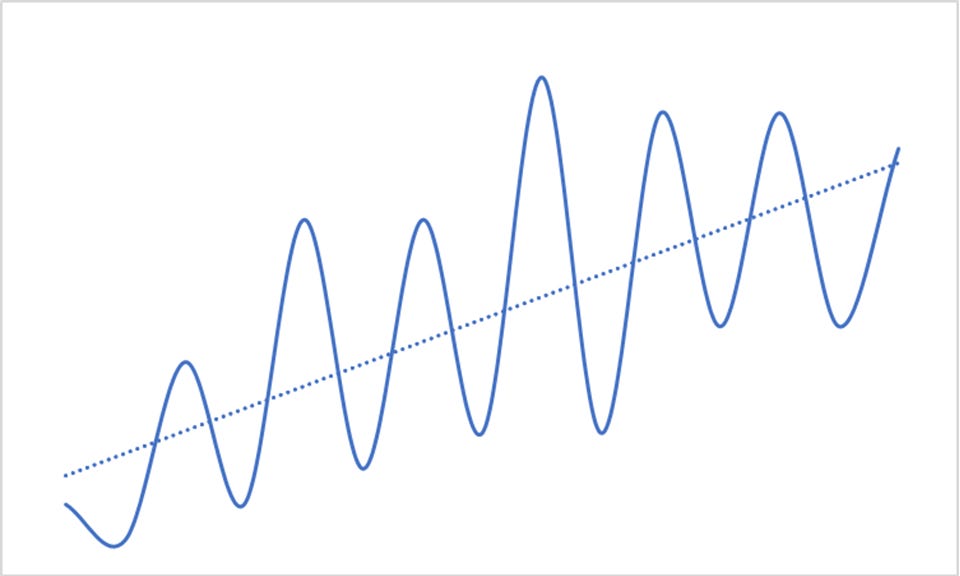

If you took statistics in college, you likely learned about Regression toward the mean, the model used to describe how variables that are extreme high or extremely low relative to the average on the first measurement move closer to the average on the second measurement.

In laymen’s terms, it describes how someone’s ability to make a half-court shot can only be adequately judged after they’ve taken a large enough number of such shots to yield a viable sample. That is, what they can do once fails to tell us anything about their talent, skill—or what would happen normally given their talent or skill.

As a lover of statistics, I take great liberties in using Regression toward the mean to describe how and when things return to normalcy. Which is what I did this summer.

Back to normal

Eight years ago, I began a practice that I had no idea I would appreciate as much as I now do: taking my daughters on Daddy-Daughter trips. They’ve been as long as 34 days and nearly 4,000 miles and as short as two weeks and 1,000 miles. But in every instance the rules are the same:

We go somewhere we’ve never been.

It’s Daddy and Daughters only. (Sorry, mom.)

There are no rules.

We’ve gone to some really cool places and done some really fun things, and in every case, my goal was the same: to soak up time with my babies. The memories we’ve made are some of the fondest I have with the girls. Each day began the same way:

I’d awaken early and work from 4 am to 10 am,

The girls would get up at 10 am and shower, and

We’d head out to enjoy coffee (and frappuccino) before enjoying a great brunch.

I recently reminded my oldest of how much much I enjoyed that time together.

“I love you. I really, really do. But no amount of enjoyment I get today from you and your sister compares to the time I’d had with you both in previous years. I’m glad I realized early on that this day would come.”

Before joining Southlake City Councilman, we would leave in June and return sometime in July. But because we don’t have meetings in July, we started leaving in late June and returning in late July or early August. The key was to have an inviolable month. Over the last two years, however, while Daddy-Daughter trips were a priority, activities would creep into our July time, and I’d resent allowing something to get in the way of our time together.

Not this year. Year 2023 was Regression toward the mean for July. Me and the girls spent most of the month outside of Southlake and outside of Texas, with one of my most fun trips being a lengthy visit to Europe with my soon-to-be-in-college oldest daughter. We visited London, Bath, Brighton and Hove. And…I attended a Lana Del Ray concert at Hyde Park in London. (I’m kinda proud of that.)

The Europe trip will go down as one of my favorites of all times, for obvious and not so obvious reasons. She’s a huge Lana Del Ray fan, so I offered to book an Airbnb and fly her and her two best friends up to see the performer in Chicago in August. Instead, my oldest sent me a text in May with these words:

“Change of plans. I want you to take me to see her in London. Just me and you.”

During our lengthy stay in Europe, we did visited dozens of attractions, enjoyed great food, walked more than 100 miles in total, had great talks, drank great coffee, and laughed a lot. But nothing beats the one thing she INSISTED we do every day.

We held hands as we walked everywhere, even on crowded London streets, including in the busy Piccadilly Circus and the narrow sidewalks of Marylebone.

Nothing tops that. (She’s always been super affectionate, even as a teen.)

The book that changed it all

The real roots of my Regression toward the mean thinking run back to Spring Break of 2013, when we took our first Disney Cruise as new Texas residents. The book I took on the trip—How Will You Measure Your Life: Finding Fulfillment Using Lessons From Some of the World’s Greatest Businesses, by one of my favorite writers and thinkers, Clay Christensen—made an indelible impact on my approach to being a father and husband.

A central point he makes is summed up thusly:

Have a strategy and purpose for your life; build up people, not simply companies; lead lives of integrity and humility; and, most importantly, choose the right yardstick.

His yardstick was that God would judge him based on the individual people whose lives he touched. He advised his readers to do the same.

“Think about the metric by which your life will be judged, and make a resolution to live every day so that in the end, your life will be judged a success.”

The book helped make real to me the importance of (a) engaging in high-ROI activities and (b) placing a priority on family. Even today, I live by one of the core tenets he professed often.

“Don’t implement a strategy, you do not plan to execute.”

In Ronell speak that means don’t waste time on activities you’ll regret giving up time with your family for.

Also…

Must confess that the visit to Memphis was dampened by all of the talk, from residents we met there, about how bad the crime is throughout the city and how we should be careful when venturing out. We didn’t stray far, but in addition to visiting Beale Street, I took a morning walk to Mud Island, and we were blown away at the experience of the National Civil Rights Museum at the Lorraine Motel.

What I’m reading

I discovered Nobel prize-winning economist Esther Duflo while listening to an interview she did with Adam M. Grant. Her novel approach to attacking poverty piqued my interest and compelled me to read Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty, which was written by Duflo and Abhijit V. Banerjee, both of whom are economics professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

I’m only 20% through the book, but already my eyes are open, thanks to some astounding, counterintuitive facts regarding the causes of poverty. Hint: It has more to do with decision making than a lack of resources. Both the data and the responses from interviews of the poor are shocking.