It’s everyone's fault. It’s no one’s fault

Why collective action problems are often at the root of what ails communities nationwide.

I’ve written in the past about collective action problems and how they are the culprit behind a high percentage of the political messes we see nationwide. For example, much of the buffoonery occurring in national politics arises from this scenario. But why, you might ask. In a word: cowardice. While fortune might favor the bold, the accolades most politicians favor—exhortation from fans and followers on social media, popularity inside their insular groups, and access to prominent, like-minded benefactors who can help their political careers—are best (that is, most easily) earned by not straying from the herd and doing what’s best for the group.

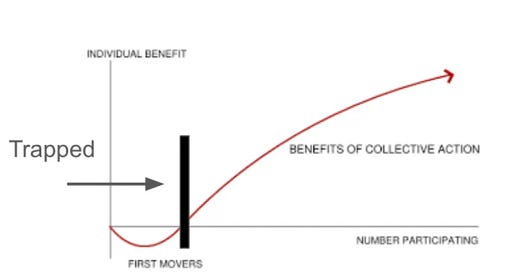

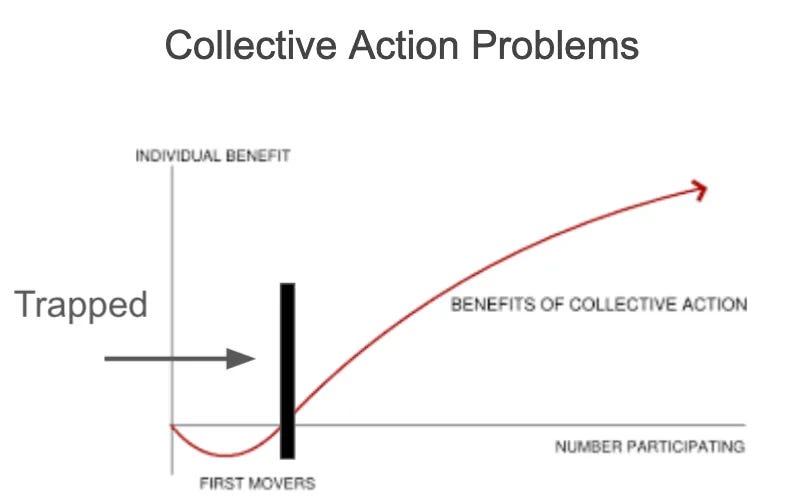

What are collective action problems?

A collective action problem, or social dilemma, is a situation where everyone in a group would benefit from cooperation, but conflicting individual interests prevent it. For example, say there are 100 people in a community, and they disagree on an issue with a 50/50 split. Because everyone in the group benefits equally when there is harmony, it would be wise for at least a few people on each side to work together to attempt to fashion a solution.

But, say a large number of people in both groups appear resistant to seeing the other sides point of view. In that case, the risk of ostracism, punishment, or banishment is too great to warrant individual members attempting to broker a sit-down. Therefore, both groups remain at loggerheads and valuable resources are wasted—all because no one is willing to risk their standing for the greater good.

The wisdom doesn’t seem conventional

Here’s an example we all understand:

In tech news, we frequently hear about the need for government intervention to curb the rise of hate speech on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook. It’s easy to ask yourself, “Why won’t these companies simply commit to comment moderation and appropriate filters for harmful content?"

They won’t touch it because doing so puts their platform at a disadvantage in reach, engagement, and potentially speed if they adopt such efforts and their competitors do not. Why take a risk when your competitors are unlikely to do so, and, worse still, my actions make me vulnerable to the market—or, in the case of politicians, their constituents. See: Collective action problem.

Why do they matter?

Closer to home, collective action problems are the culprits behind many of the most vexing issues in our local communities, too. We disagree, even over seemingly simple issues, then instead of seeking common ground, we sow division that festers unabated. Residents of these now-divided communities are often aware that they agree more than they disagree, but no one dares risk seeking common ground lest they face scorn from members of their own so-called side.

The remedy: Courage and a willingness to believe in the value of the collective above any potential loss, even if that loss is costly personally, politically, or professionally. While, yes, I think leaders willing to traverse these waters are rare, they do exist. Better still, even more leaders will likely show themselves under the right circumstances and given proper incentives.

Why do I care about collective action problems?

I grew up in a heavily segregated town, where there were clear racial lines separating churches, housing, and businesses. Whites and Blacks went to school together; that was the totality of their interactions. There was no commingling to speak of, especially of the religious or business variety.

Until my junior year of high school. A Black graduate opened a business on the northernmost end of town adjacent to a popular game room and abutting the local hamburger joint. I remember visiting the business for the first time and talking to the owner, who was six years my senior, and being at once proud and scared out of my mind.

“I don’t leave here at night by myself,” he said, echoing sentiments I heard often from folks aware of my hometown’s history.

Months later, while visiting the business, I overheard the owner talking about his concerns and a few weird interactions he’d had with unfriendly residents.

“If not me, then who?” he said to a large group of his classmates. “I know they don’t want me here. I also know that unless or until someone like me opens a business, there won’t be one in this part of town. It’s a risk, but I’m looking at the potential gain.”

Remarkably, the business thrived and was frequented by both Blacks and Whites. This never would have happened had he allowed the fear of opprobrium from either side to blind him to the opportunity beyond the risk.

Our communities need more leaders like Craig Hart. Sadly, they are in very short supply.