From Chicago's south side to the ivory towers of academia: The making of Glenn Loury

Economist Glenn Loury overcame drug addiction and infidelity to become one of the foremost public intellectuals and social critics of the 21 century.

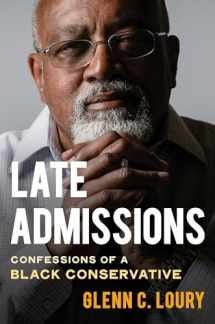

Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative

By Glenn C. Loury

Grade: 98

It’s fair to say that I have Glenn Loury, currently the Merton P. Stoltz Professor of the Social Sciences and Professor of Economics at Brown University, to thank for discovering political conservatism. His writing and thinking have had a huge influence on me since college. So it was with great anticipation that I hurriedly read his new book, Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative. And though I was very familiar with many of the details of his life, his thoughts, and his work, I found the book—written in a narrative style I’m very familiar with—as compelling as it was brickbat-to-the-head candid.

Loury, now 75, is an accomplished, esteemed economist, having earned his way from the south side of Chicago to be educated at and employed by some of the country’s most elite universities, with MIT, Harvard, and Northwestern among them. But, as he shares in vivid and often painful details, the sailing has been far from smooth as, along the way he’s struggled with drug addiction, was an unmarried father of two kids by age 19, once faced charges of abuse, had an on-again, off-again relationship with his faith, and moved back and forth and back politically.

Having read his work for more than 25 years, I find myself often reminding friends, many of whom have only recently discovered Loury through his popular podcast with John McWhorter (another favorite author of mine), that, should they read his earlier works, they’ll discover a different Glenn Loury, one who started out rather conservative, then in the early aughts became more liberal, and who is now—and has been for years—-quite conservative.

A little backstory

In college, I read every book on the shelves under Black History, consuming works from Ellis Cose, Cornel West, Bell Hooks, William Julius Wilson, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Shelby Steele, Claude Steele, Thomas Sowell, W.E.B. Dubois, Larry Ellison, Orlando Patterson, Ken Hamblin, Booker T. Washington, Walter Williams, and, yes, Glenn Loury, among numerous others.

Something about the conservative argument—that race is neither a defining characteristic nor a permanent impediment to the success of Black Americans—resonated with me, especially when I read the words of Black conservative thinkers, such as Clarence Thomas and Sowell, both of whom hailed from the Deep South, where racism was pervasive.

A voice of resonance.

Loury, however, stood out because of his deep intellect and his willingness to wrestle with, for—and sometimes against—his conservative beliefs, especially as they led to difficult conversations with family members. More than two decades ago a New York Times article, which I still have in my possession, illustrated how Loury’s conservatism caused some family members to look askance at him.

“‘There came a point when I couldn't look my own people in the face,'' Loury says, explaining his evolution. “Everyone else had a place to go. Some would go to Jerusalem. Others would go to Dublin. You see the metaphor. Where would I go? I came back to Chicago and talked to my uncle about what I was doing. There was a reproachful look in his eyes, a sadness. He said to me, 'We could only send one, and we sent you, and I don't see us in anything you do.' Eventually I realized I couldn't live like that.'”

I read that quote in January of 2002; I know the feeling all too well, though not from family members.

A man determined

Throughout Late Admissions you’ll read numerous stories highlighting an only-in-America story of how a young Black kid with a strong network of family members rose from a segregated, economically depressed neighborhood to become a math prodigy who’d get degrees from Northwestern and MIT, and go on to hold teaching positions at Michigan, Harvard, Boston University, Northwestern, and now Brown.

I knew much of the details about his teaching and his politics, but the depth of his struggles with drug addiction and promiscuity, both of which threatened to unravel his career on numerous occasions, was new to me. Reading about his adultery was anger-inducing, especially for someone with as bright a future as he had as a young economist. But, it’s hard to fathom Loury, a grandfatherly figure today, walking the streets, late at night, to score crack then smoking it in his car or his apartment.

One of the most harrowing stories involves Loury smoking crack in his office at Harvard University as his mentor and friend, Kenneth Arrow, a Nobel Laureate, knocked on the door. The book is filled with details such as this, as the author, who held true to his desire to write a candid, warts-and-all story, holds back few details.

What might have been

Being as familiar as I am to Loury’s writing and his story, I came to the book with an agenda: I wanted to learn the details of his political movements, his struggles with a life of faith, and his career arc—that is, he started out as someone seemingly on the path to a John Clark Bates Medal, given to the top young economist each year, but made the move to African American studies.

I’m not sure he answered satisfactorily either of the questions I had. I’m left to assume that his conservative-then-liberal-then-conservative-again movement was owing to, as I often say of Black conservatives, coming to see the world as it is, not as it’s often described to be. On the topic of Christianity, it’s apparent that he feels the tug to believe in a higher power, authority, but as he’s written elsewhere, “it never stuck.”

On the subject of his career, however, he does offer some clarity, painful as it might be. Loury said that, despite all of his accomplishments, accolades and recognition from top economists in the field, the move to Harvard in 1982 awakened in him a sense of imposter syndrome, whereby he wondered if he really could compete at the highest levels with the brightest minds in the field. That’s quite an assessment for a young man whose strength was abstract math modeling, one of the toughest and most cutting edge areas of economics at the time.

“I choked,” he said about being around the brilliant minds at Harvard—of which he was one.

He then moved from economics to the Kennedy School of Government and set off on a course to become one of the brightest, most influential public intellectuals of the 21 century. His writings, talks, and his popular podcast with linguist John McWhorter are beloved the world over for their thoughtful, analytical critique of race.

You should read Late Admissions not because I loved it, but because I think you’ll enjoy it and learn from it as well.