Two-minded thinking revealed

A Nobel laureate helps us make better decisions by sharing what's happening inside our heads.

By Daniel Kahneman

Grade: 98

The book Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman, has for several years suffered from my addiction to delayed gratification: I refused to read it until such time as I knew I could thoroughly immerse myself in the content on its many pages. Having finished it last weekend, I’m both happy I waited and mad at myself for only now enjoying the brilliance the author shares in the book. Kahneman, a Nobel laureate and a towering figure in economics, distills decades of research into an accessible narrative that challenges our understanding of how we think.

The core of the book: system 1 and system 2 thinking

Kahneman introduces the idea of two modes of thinking: System 1, which is fast, automatic, and intuitive.

“It operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control.”

System 2 refers to slow, deliberate, and analytical processing.

“[It] allocates attention to…effortful mental activities that demand in, including complex computations.”

For example, when you quickly read a word on a billboard or instinctively brake to avoid a pedestrian, that’s system 1 in action; discerning complicated text or solving complex math problems requires that system 2 take charge.

Throughout the book, the author continually makes the case for how, by developing an understanding of system 1 and system 2 thinking, we can all become not only more aware of the flaws in our logic, including cognitive biases, but we can also become better critical thinkers.

What I enjoyed most

I’ve written before of my love for behavioral economics, which combines economics and psychology and helps to explain our decision-making far better than classical economics ever could.

Kahneman goes deep into detail on several of the cognitive biases we’re all subject to fall under the spell of. I list of a few of my favorites below:

Anchoring effect - Refers to relying too heavily on the first piece of information we encounter. For example, in negotiations, an initial offer typically sets the stage for the final agreement. If the starting bid is high, the final price will likely be higher than if the bid started low, regardless of the actual value of the item being considered.

The Halo Effect - This bias occurs when our overall impression of a person influences our judgments about their specific traits. That is, if someone is attractive, we might also assume they are more intelligent or competent, even without evidence supporting these assumptions.

Availability Heuristic - This concept explains how people estimate the likelihood of an event based on how easily they can recall similar instances. For example, after seeing a news story about automobile pile ups on a popular highway, someone might overestimate the dangers of driving on that roadway, even as the data shows it to be far more safe than other similar stretches of highway.

Prospect theory - This theory explains how people make decisions involving risk, showing that we tend to fear losses more than we value gains. Consider an investment scenario: the pain of losing $10 is more intense than the pleasure of gaining $10, leading people to avoid risks even when potential rewards outweigh the risks.

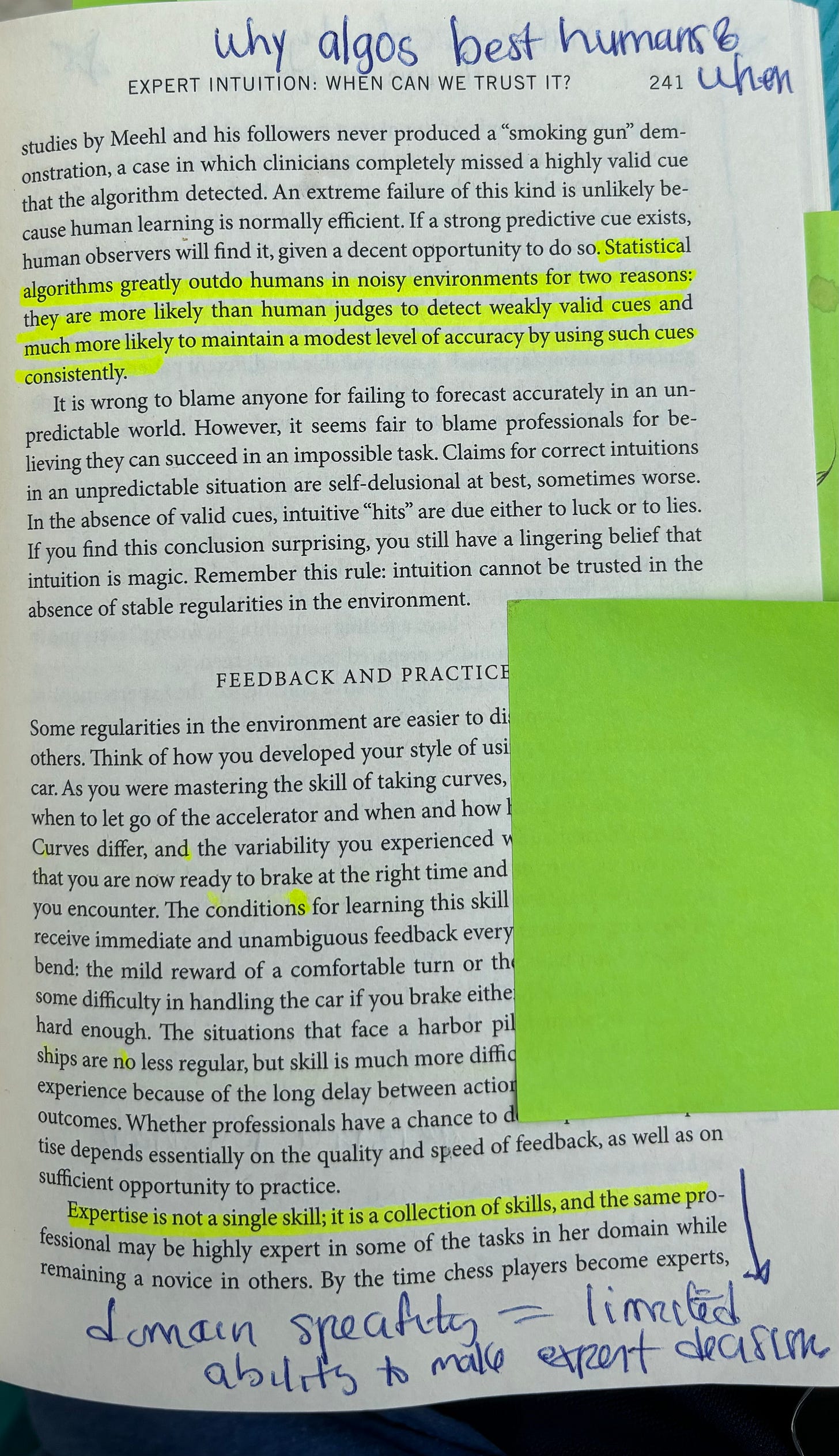

One of my favorite parts of the book: “Expert Intuition: When Can We Trust It?”

Selfishly, I wish everyone was forced (maybe that’s putting it too strongly) to read this chapter, especially the section on “The Environment Of Skill.” In it, the author highlights the specific conditions under which experts’ intuition is likely to be more accurate:

“An environment that is sufficiently regular to be predictable, and

“An opportunity to learn these irregularities through prolonged practice.”

“Remember this rule: Intuition cannot be trusted in the absence of stable regularities, in the environment.”

I appreciated this because it gets at something that’s long been an annoyance of mine: Smart people who rely too heavily on their own knowledge when (a) circumstances warrant prioritizing objectiveness and (b) they have little knowledge in a given domain.

“Expertise is not a single skill: it is a collection of skills, and the same professional may be highly expert in some of the tasks in her domain while remaining a novice in others.”

This calls to mind the aphorism “Stay in your lane.”

Who should read Thinking, Fast and Slow?

Even if you’re not a behavioral econ fan like me, anyone will benefit about the psychology at the root of much of our decision making. Kahneman’s accessible writing, plentiful practical examples, and the tools he provides for helping readers better understand the world around them easily makes the book a worthwhile read. In fact, I plan to re-read it, in part to better understand the dozens of concepts that I underlined on the first pass but hope to understand thoroughly.