Writing the book on Southlake?

National author pens book highlighting what happens when communities don't tell their stories.

TL;DR:

Unfortunately, the book misses several key points and fails to connect others. For example, instead of blindly assuming that Southlake’s so-called division resulted from a “hyperlocal version of what’s known as the Great Replacement Theory,” the author might have asked, “How could this have been avoided?” However, he deserves credit for the yeoman’s effort he put into researching and writing a heavily detailed, very well-written book.

Setting the stage

I am very well aware that this book and this topic are white-hot right now. I’d like to make a few things clear at the outset, then ask for a small favor. First, I created this blog to share my thoughts and ideas on a wide array of topics, including books, business, and yes, politics. It’s my social media, if you will, as I have always despised Facebook, Twitter, and the like for how they are used and misused.

I, as a rule, do not write about the goings-on in Southlake, in large part because I’m too close to the politics here, but also because I don’t much care about inserting myself in politics. (There was a time when that was not the case; that time has passed.) I’m a local elected official; I am not a politician. I write this because a lot of new folks signed up for the newsletter after a recent post was shared in a private group, so I need to do some level-setting.

About the book

While I was tempted to refrain from writing about the book, I did request a review copy to read and review, so I at least owe it to the publicist to do just that. Because I have intimate knowledge of most of the areas the author covers related to Southlake—the book doesn’t just talk about what’s happening in the Emerald City—I’ll have to pare my coverage for two reasons:

The review would be 10,000 words, and

To keep my powder dry in the interest of (possibly/maybe/likely) writing a book that tells an accurate (more on this below) story of what really happened, why, and how it could—and should—have been avoided.

A small favor

Please do not share this post on social media. I’m not interested in the attention it would bring, and I’m not writing it for anyone but the readers of my newsletter and those they share it with. Social media is dirty air to healthy discussion.

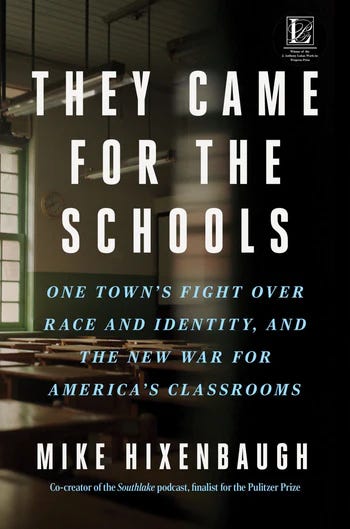

They Came for the Schools: One Town's Fight Over Race and Identity, and the New War for America's Classrooms

By Mike Hixenbaugh

I have to give it to the author for writing a heavily researched, nuanced, and detailed book that includes a lot of historical detail for context. And while, yes, the book is mostly focused on Southlake, a city from which he has made quite the name for himself over the last four years, it’s actually a deep dive into what he sees as an attempt by a political faction to impart their views on public education.

“Southlake isn’t merely a microcosm of the political upheaval threatening public education nationally; it became a proof of concept on the far-right. The highly coordinated campaign to impose conservative Christian viewpoints in Southlake schools became a model—or cautionary tale, depending on who you ask—that has since been replicated in suburbs all over the country, from Pennsylvania to Tennessee to Missouri and beyond.” (He shared these comments during a Q&A with the publicist, whose printed notes accompanied the book.)

Background

I’d be disingenuous if I didn’t admit to having very personal reasons for wanting to read the book. Chief among them, I suspected he would get obvious things wrong, and he did. (I can assure you that no one on earth has more accurate information than me on the substance of the book as it regards Southlake during the period from October 2018 to November 12, 2020.) Additionally—and predictably—he wrongly conflated residents’ disapproval of a flawed plan with their supposed intransigence toward tackling issues a number of families faced in the district.

But he also got some simple things wrong. For example, he refers to me as a “Black father who would go on to serve on the city council…and [whose] wife, a white woman… .” Then, later he writes, “Smith was the Black father of biracial girls.” Neither of these statements is true. These are simple, easily verifiable facts that would require no more than perusing my public Facebook page to verify. (I don’t assume any malicious intent; I assume he felt I fit the stereotype.)

But that’s just the beginning of what I assumed he would get wrong. For example, in March of 2023, Hixenbaugh reached out to me for comments, asking if I would be willing to record a phone conversation for his upcoming book. He wrote that he planned to mention comments I made in 2018 before the board and what he termed my initial support for the vote to accept the plan, as detailed in the texts with Michelle Moore, and what he calls my decision later to publicly oppose the plan after speaking with residents.

Here’s what I wrote via email:

“I was never, even in the texts, in support of CCAP as a plan; I was supportive of Ms. Moore presenting the plan without asking for a vote. That was and is my position. ... I was, then and now, supportive of the folks who worked hard to help kids in the district, but no one on the DDC was qualified to deliver a plan that would then be rubber-stamped by the board. The plan should have been viewed as, at best, suggestions, not anything that would be acted upon. My goal was to get Ms. Moore to see the benefits of passing out the plan, having the board review it, and, at some later date, share their thoughts. That was my goal entirely. I was never in support of CCAP; I didn't need to talk to anyone about that fact.” (For the record, I shared these thoughts with multiple administrators in early 2022, well before the plan was unveiled.)

I’ve written in great detail on this topic, so I’m not going over it again here, but suffice to say, no one who knows me would ever think they could change my mind if I thought what I was doing was the right thing to do. See again: I am not a politician.

Southlake the concept

If you love Southlake as I do, you are not going to enjoy the book. Many are likely—certainly after reading the latter third of the book, which discusses what’s happening in Southlake as a foregone conclusion, tying it to politics nationwide—to throw it across the room in disgust. However, while there is a tendency to immolate the author for trying to destroy our town, I don’t think that’s correct.

That’s not how the media works.

Media needs clicks, eyeballs. Southlake, in and of itself, does not generate clicks. (Google Trends proves as much; more on that in another post.) But Southlake as an avatar does get clicks. Lots of them. Why? Because Southlake is a concept: Wealthy, exclusive, large homes on huge lots, high-achieving kids, and top schools.

Myriad Americans aspire to live in such a place. However, a large (very large) segment of the country sees something more sinister: White and excluding of poor and minority families. Even when they learn that the city and its schools are far more diverse than it seems and many of the largest homes, top businesses, and highest test scores are owned by folks of East Asian descent, they come back with, “Yeah, but why are there less than 2% Blacks?” as readers are prone to write to me.

In their minds, Southlake and communities like it are the apotheosis of something they are given license to despise. Hixenbaugh falls for this lazy logic early in the book when writing about Southlake’s formative years.

“What none of them acknowledged at the time—at least not publicly—was that, in America, income is a proxy for race, and that by keeping Southlake wealthy, its leaders were, in effect, keeping it white.”

Read that again. That’s akin to saying “Cadillac, by keeping the 1965 DeVille at $5,000, was, in effect, consigning the vehicle to whites only.” If you begin from this viewpoint, or use this framework, the concept you’ve created is going to go undefeated, no matter how flawed the premise. (I’m going to write a blog about the inability of defeating a concept in the future.)

Missing the larger story

Therefore, it’s easy to see how Hixenbaugh uses the rest of the book to make the case for how Southlake is representative of how white conservatives take over communities to impart their ideals. What I most cared about when reading the book were the events that took place before August 3, 2020. The vote taken that night unnecessarily set off a chain of events that proved cataclysmic, with shock waves still rippling through the city.

I do applaud the author for detailing the rich, storied history of Southlake against the backdrop of what was happening nationally in the 1950s and ‘60s. He correctly shares how the city attracted people who wanted a more rural way of life but in the suburbs, and how community leaders and residents worked to secure the land and ensure that the city would become and, likely remain, what it was conceived as: A place with a “rural feel,” having a “strong collective identity,” where everyone is a Dragon, and where “it felt like a family,” as one Black family described Southlake upon moving here 20 years ago.

As he wrote, and has been widely chronicled, there were several reported racial incidents involving Black parents and students in the early years, and then again in the mid-90s at a football game, but the story really takes a turn when the author discusses three incidents that took place in 2018 and early 2019:

A homecoming DJ playing the “Mo Bamba” song, with students singing the version containing the N-word,

A video of kids chanting the N-word,

A video of kids saying the N-word while driving

It couldn’t have gone any other way

These three incidents set the course for the school district to form a diversity group that would help them navigate these waters until things started unraveling in July 2020. He recounts what happened next—contentious board meetings, legal charges, a lawsuit, elections, a PAC was formed, public bickering ensued, a simmering division found a home, etc. He uses the rest of the book to tie what was happening in Southlake to what’s happening across the state and the country, with schools being ground zero for parental infighting.

Candidly, the back half of the book was of far less interest to me. My views on parental rights, politics, and religion were formed years ago, so while I appreciated his attempt to tie together some obvious connections, I was less interested in his refusal to see issues from both sides. For example, parents absolutely have the right to push back against what they see as indoctrination—whether social, cultural, political, or religious—in public schools.

After all, even left-leaning parents like The Atlantic’s George Packer have decried how schools’ focus on identity separated kids by oppressed and oppressor and led to daily interactions that were overrun with kids having to “check their privilege” by checking a box highlighting how their racial status led to microaggression against a fellow students.

I don’t recall the author making this point. And, not to be a bothsides-er, but that stands, in my eyes, whether you’re on the left or the right.

Saddest thing about the current state of school-related politics in our town is knowing we didn’t have to be here, but once certain decisions were made, we were always going to get here.

Final thoughts—for now

When researching and writing a book, certainly one that’s likely to be viewed as controversial, it’s imperative that the author continually asks himself or herself “What am I missing?” “Where are my blind spots?” and the like. With They Came for the Schools, it’s somewhat understandable that there would be some glaring holes given that he was mainly talking to folks on one side of the issue and relying on public comments from the other side.

I’ve now gone through the book nearly four times. With each passing, I keep wishing the author had done what a newspaper editor once challenged me to do.

“You have to learn to ask the next question,” he’d say. “A meaty story, one full of details, is easy for any reporter to write. You have to ask the next question to get at the story behind the story—that’s the real story.”

I wish Mr. Hixenbaugh had followed this advice.